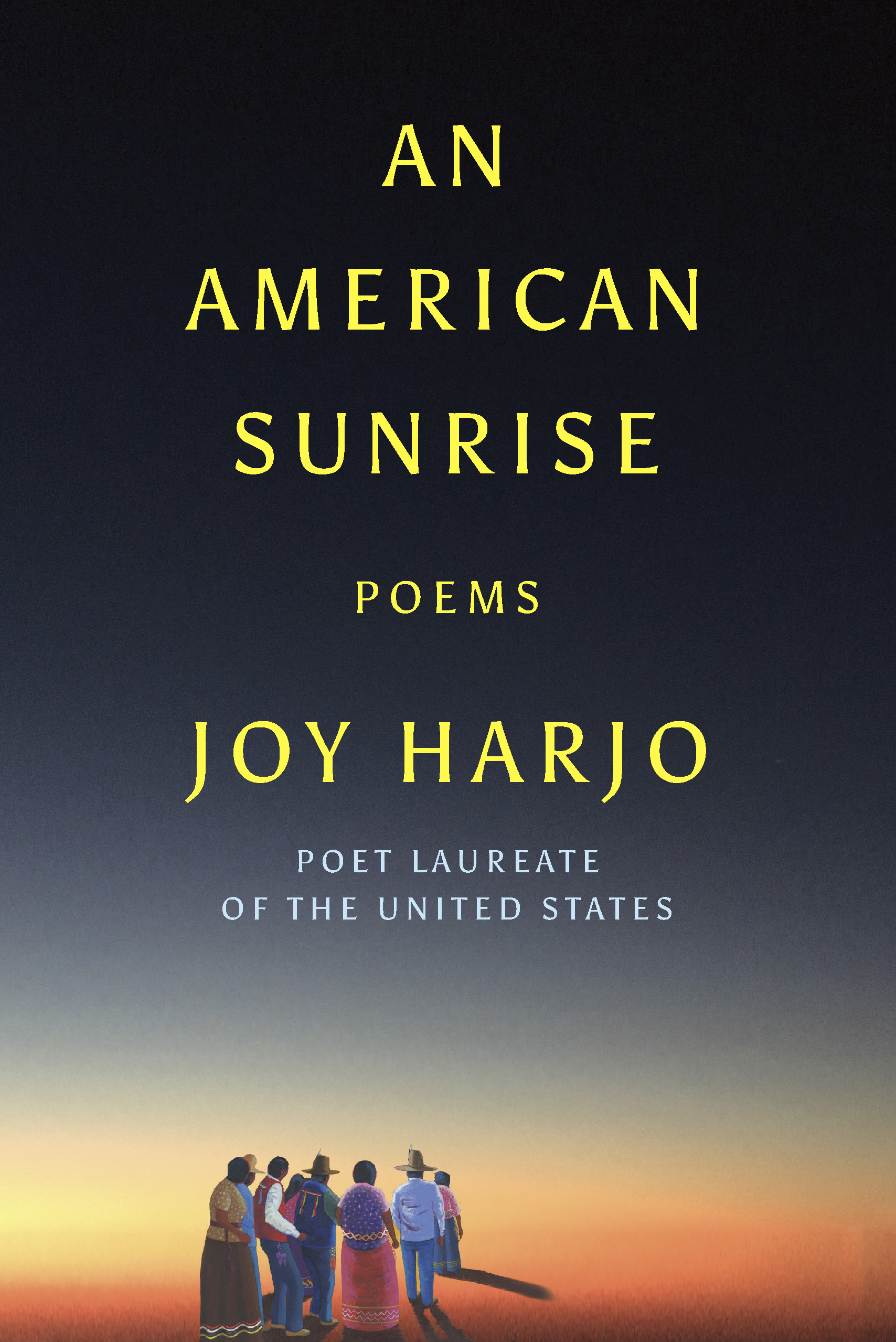

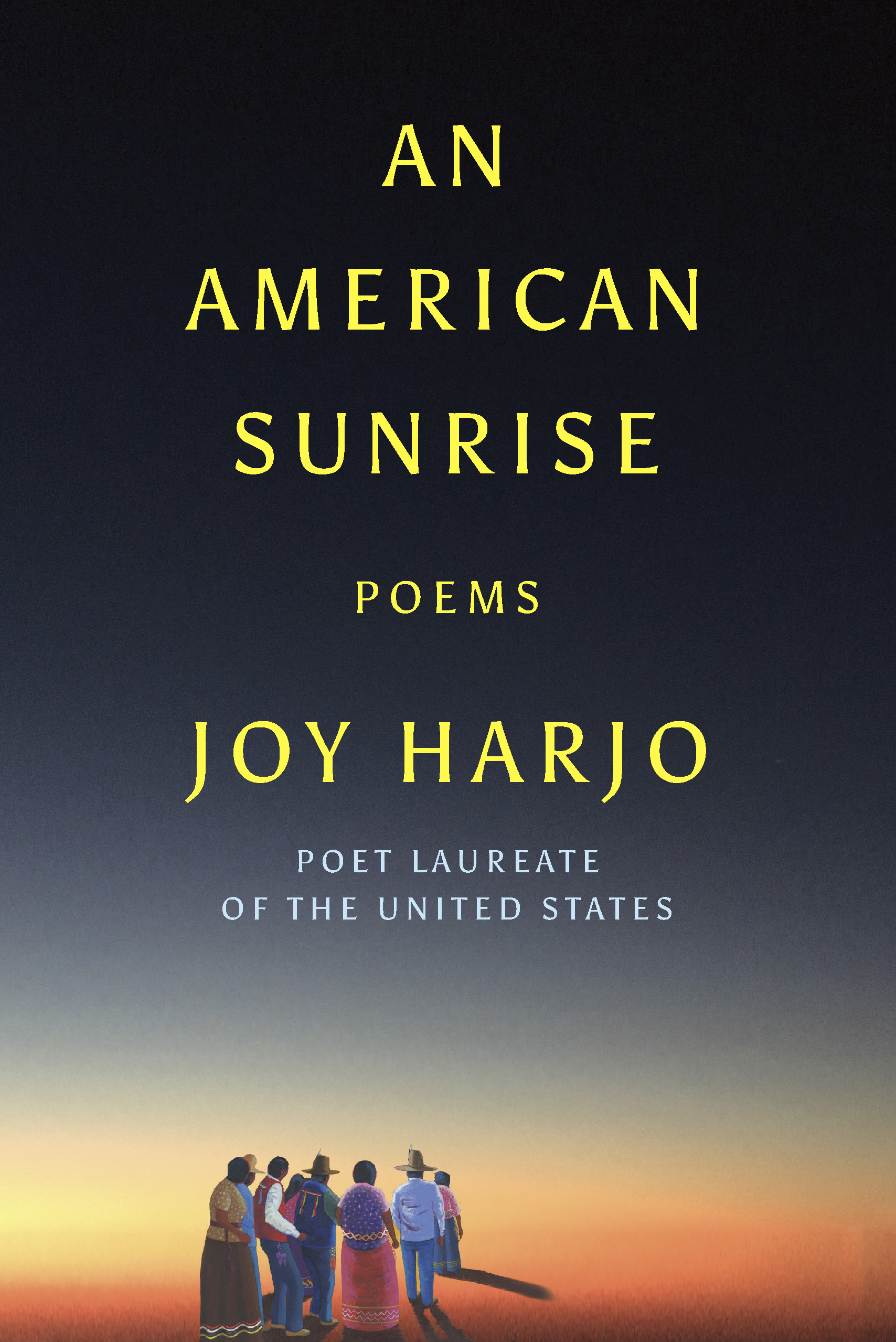

Writer, musician, and current Poet Laureate of the United States Joy Harjo was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and is a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. An American Sunrise—her eighth collection of poems—revisits the homeland from which her ancestors were uprooted in 1830 as a result of the Indian Removal Act. It is a “profound, brilliantly conceived song cycle, celebrating ancestors, present and future generations, historic endurance and fresh beginnings,” wrote critic Jane Ciabattari. “Rich and deeply engaging, An American Sunrise creates bridges of understanding while reminding readers to face and remember the past” (Washington Post). Harjo’s many awards include a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas; the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America; the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets; and two National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowships. “To read the poetry of Joy Harjo is to hear the voice of the earth, to see the landscape of time and timelessness, and, most important, to get a glimpse of people who struggle to understand, to know themselves, and to survive” (Poetry Foundation). “Joy Harjo is a giant-hearted, gorgeous, and glorious gift to the world," said author Pam Houston. "Her belief in art, in spirit, is so powerful, it can't help but spill over to us—lucky readers.”

“I returned to see what I would find, in these lands we were forced to leave behind.”

– Joy Harjo, "An American Sunrise"

"Don't worry about what a poem means. Do you ask what a song means before you listen? Just listen." —Joy Harjo

To open Joy Harjo's An American Sunrise (W.W. Norton, 2019) is to be immersed in the power of nature, spirituality, memory, violence, and the splintered history of America's indigenous peoples. To read her poetry is to be drawn into the rhythms, sounds, and stories of Harjo's Creek heritage. In this collection, she returns to Okfuskee, near present-day Dadeville, Alabama, where her ancestors were forcibly removed by the Indian Removal Act of 1830. “It came directly out of standing and looking out into the woods of what had been our homelands in the Southeast before Andrew Jackson removed us to Indian Territory,” said Harjo in an interview with TIME. “I stood there and looked out, and I heard, ‘What did you learn here?’”

The collection is prefaced with a short prologue about her ancestors’ removal and a map of the Trail of Tears, the difficult series of trails over 1,000 miles long, taken by foot during their forced relocation. Several thousand indigenous people died as a result of this journey. According to its caption, the map depicts just one of many trails the Muscogee Creek Nation took to “Indian Territory”—now Oklahoma—“just as there were [many trails] for the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole and many other tribal nations.” “We were forced to leave behind houses, printing presses, stores, cattle, schools, pianos, ceremonial grounds, tribal towns, churches,” noted Harjo in the prefatory prose. “We witnessed immigrants… taking what had been ours, as we were surrounded by soldiers and driven away like livestock at gunpoint.”

In the beginning poems, Harjo “doesn’t just honor the people, creatures and landscapes that were lost,” wrote the Washington Post. “She embodies and embraces them.” “History will always find you, and wrap you / In its thousand arms,” says the first poem, “Break My Heart” (p. 3). “Exile of Memory”—a long poem broken into several short sections—is a meditation on historical trauma and weaves together memories of the past, present, and future. In the opening section, Harjo is warned not to return to her ancestral homeland: “You will only upset the dead” (p. 6). Other sections tell of the intergenerational trauma. “We are still in mourning” begins one section (p. 9). The children were “given prayers in a foreign language to recite / As they were lined up to sleep alone in their army-issued cages.” Other sections recount her experiences revisiting her ancestral homeland with her husband. “We could not see our ancestors as we climbed up / To the edge of destruction / But from the dark we felt their soft presences at the edge of our mind / And we heard their singing” (p. 16). In some sections, the speaker feels resolved in the natural beauty that still remains, in the trees and the “herd of colored horses breaking through time.” (p. 19). “The final verse is always the trees. / They will remain” (p. 14).

Woven throughout the collection are passages of prose written by Harjo, as well as excerpts, lyrics, and quotes from outside sources that help paint the complex backdrop to her poems and add a chorus of voices to the collection as a whole. “The Road to Disappearance” (p. 36) is an excerpt from an interview with Siah Hicks (Creek) on November 17, 1937, who recounted what the older generations said about leaving their land behind. “The Indian is now on the road to disappearance,” she recalled them saying. And “Mvskoke Mourning Song” (p. 51) is from an interview with Elsie Edwards on September 17, 1937, and tells the story of Sin-e-cha, who was aboard the steamboat Monmouth that carried Sin-e-cha and her tribal town during their removal, and which sank in the Mississippi River. Emily Dickinson’s poem “I’m Nobody! Who Are You?” appears after a poem that is dedicated to her, and includes the short passage, “Emily Dickinson was six years old when Monahwee and his family began the emigration to the West” (p. 60).

Harjo’s grandfather from several generations back, Monahwee (also spelled Menawa) is a recurring figure in the prose passages and “My Great-Aunt Ella Monahwee Jacobs’s Testimony” (p. 63). According to these passages, Monahwee was second chief of the Creeks, one of the chiefs of the Red Sticks, a group that worked to preserve traditional indigenous culture. He fought Andrew Jackson’s forces in the 1814 Battle of Horseshoe Bend, opposing American expansion; “had a reputation for valor and military skill;” and was also a “doctor of medicine” (p. 65). One passage reads, “It is said that Monahwee got his warrior name Hopothepoya (Crazy War Hunter) from stealing horses in Knoxville. Knoxville was in traditional Mvskoke territory, therefore, the horses were not technically stolen. They were liberated” (p. 67).

Many poems open a dialogue with Harjo’s ancestors and tribal history. “I grow tired of the heartache / Of every small and large war / Passed down from generation / To generation,” the speaker says in “The Fight” (p. 21). “How to Write a Poem in a Time of War” takes on the voice of ancestors and imagines them trying to write a poem while European immigrants “began building their houses all around us and demanding more. / … started teaching our children their god’s story, / A story in which we’d always be slaves” (p. 48). Searching for origins and understanding are at the heart of many of these poems. "I am driven to explore the depths of creation and the depths of meaning," said Harjo in an interview with Terrain. "Being native, female, a global citizen in these times is the root, even the palette.”

In other poems, Harjo’s personal life is at the forefront. In “Washing My Mother’s Body,” Harjo’s speaker imagines bathing her mother’s body one last time after her mother’s death, something she didn’t get a chance to do. “I return to take care of her in memory. / … As I wash my mother’s face, I tell her / how beautiful she is, how brave, how her beauty and bravery / live on in her grandchildren” (p. 30). “I am tender over that burn scar on her arm” she writes, “From when she cooked at the place with the cruel boss.” In this poem, “ritual becomes visionary as the mother’s body becomes a crossroads of tenderness, suffering, joy and oppression both intimate and public” (New York Times). “My Man’s Feet” is an ode to Harjo’s husband, “the sure steps of a father / … when he laughs he opens all the doors of our hearts” (p. 71). The poem “Directions to You” (p. 22) is addressed to Harjo’s daughter, Rainy Dawn Ortiz. “Rabbit Invents the Saxophone” (p. 75) is a creation story of the saxophone—an instrument played and beloved by Harjo and her grandmother.

Throughout the collection are poems that take on different forms. “Weapons,” (p. 27) is broken into sections by color: black, yellow, red, green, and blue. “Mama and Papa Have the Going Home Shiprock Blues” (p. 37) is a series of short songs based on several painting titles by indigenous artist T.C. Cannon. “For Those Who Would Govern” (p. 74) is a sequence of questions posed to anyone in a position to govern. “Advice for Countries, Advanced, Developing and Falling” (p. 79) is a call and response poem, where the speaker’s statements are followed by responses from an imagined audience. The title poem, “An American Sunrise,” (p. 105) is a golden shovel, a poetic form invented by the poet Terrance Hayes in which the last words of each line are words taken from a Gwendolyn Brooks poem. The end words in “An American Sunrise” are taken from Brooks’ famous poem “We Real Cool.”

The poems in An American Sunrise are at once praise and song and facts plainly spoken, “from a deep and timeless source of compassion for all—but also from a very specific and justified well of anger” (NPR). They open many doors, into personal and historical heartache and survival, joy and tears, stolen land and the celebration of nature and loved ones. They offer a “stark reminder of what poetry is for and what it can do: how it can hold contradictory truths in mind, how it keeps the things we ought not to forget alive and present” (NPR).